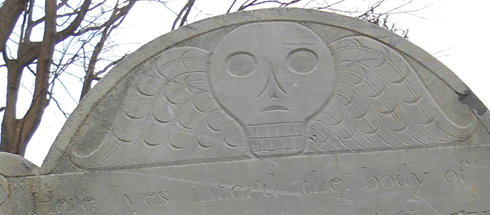

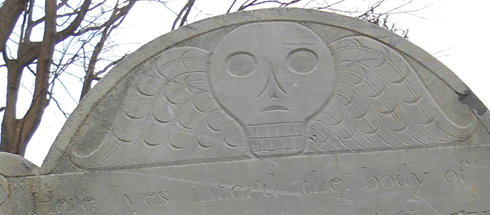

Long Island slate headstone from Colonial America (c. 1764) of an other-worldly figure.

L.I. does not have stone quarries, where is this tombstone from?

(If you do visit a cemetery, obey all regulations and posted signs. Be respectful.)

Without movies, burial grounds were a good show (still are)...

“Behold, and see, as you pass by.

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, you must be.

Prepare for Death, and follow me.”

This was a epitaph above graves, that conceivably could be granted a copyright, I saw this inscription on three, antebellum (pre-Civil War) headstones. The ominous tone suggests one should limit their visits here, because two centuries ago, people were very uncomfortable with the subject of death. Of course, now, everyone can appreciate that death is simply an unfortunate, sometimes tragic, part of life. No one lives forever, right?

How did they bury corpses in wintertime, if the ground was frozen solid? Was the body put aside until there was some thawing of a kind? Could it have been cremated, unbeknownst? You’re thinking: “Gee, this guy could have been a mortician.” (Seriously though, I like to kid.)

To read the headstone, be cognizant that “s” is often written as “f.” To view any of them close-up, right-click one, then select “Open in New Tab.” Hold down the “Ctrl” key, then use the scroll wheel to magnify. Or just do the same to this entire page, by using “Ctrl” and the scroll wheel.

Here is a headstone with excellent calligraphy even though it was carved in 1749 (pre-Revolutionary War). Where did they get the shale, who could carve with such intricacy, and how could a 38-year-old afford this tombstone? There is no listing of kin. (John Slatterly did not have a middle name.)

Was it a fake death to avoid paying taxes to King George, then King of England? Dead men cannot pay taxes, and his money could conceivably have all went to the headstone. (While there is not any record of fake headstones, the thought did occur to me.)

The pale-blue shale, the red sandstone, and the white marble, must have been brought by horse and carriage from places like the Granite State, New Hampshire (or Europe, although that is improbable). These materials are not local to sandy Long Island. Shale, sandstone, then marble, was the order of longevity (and likely cost) of the headstone material. Shale had the finest engraving work, marble was the most granular.

Women had their husbands name included on their headstone. Men conveyed any societal rank to the wife. Husbands did not name their wife on their rock memorial.

As mentioned at the top of this page, “F” often replaced “S” in both writing in books, and engraving on headstones. “Lies interred” was spelled “Lyes inter’d.” “The” was spelled “ye”, with a superscript, “ye”. This may have been to deter slaves trying to read. New York State officially ended a weak slave economy in 1827.

Many headstones were sketchy on dates. A few may have understood the significance of the Vernal and Autumnal Equinoxes in determining dates. Most probably did now know what exact day it was, as calendars were not available (for the most part, neither were dictionaries). On the monuments, there are dates of death, but not so often birth dates. They knew the age at death much more than the number of years with any fraction. Their math skills were also likely weak, they would have difficulty calculating the length of life between birth and death.

One burial grounds was in the woods. Although Huntington Village was just eight miles distant, those buried here may have never seen it. Pioneers could easily have spent just about their entire life within the boundaries of their farm. Even going to a church would be a rather arduous slog. Being this isolated could make a relationship with god not the generally accepted god as one’s friend, but rather god as authority figure.

Several headstones of soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War, refer to the deceased as “Associators,” and not Revolutionaries, or Patriots. (Upon further research, associators were Tories, British Loyalists.)

Long Island did have Loyalist, British sentiment (as opposed to New England which had a strong Patriot contingent — Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, etc.). Nathan Hale, though, was lynched (in Halesite, Long Island) for not supporting Britain. His last words were: “I only regret that I do not have more than one life to give for my country.” (Then, with a second life, he could be hung, and still go back to being a farmer, or whatever? Just saying.)

My favorite was the one headstone adorned with a fleur-de-lis. The French inscription was perhaps the only one on the hill not in English.

At the Huntington Village Burial Grounds, the main boulevard, the main promenade, was once not by the parking lot, but on the other side of the Historical Society building, which was built in 1892 — a late-comer to this hill with antebellum headstones. The new, Best in Show were buried by the parking lot, West of the earlier show-stoppers. In other words, the parking lot was a later addition, paved around the cemetery.

This appears to be a very interesting indictment of early medical malpractice — “died...by inoculation” (the headstone was broken into two halves, as if to avoid implicating the wrong-doers):

In Memory of

Peleg, Son, of

Thomas & Mary

Conklin

who died

[broken in half here]

of the Small pox

by Inoculation

Jany 27th. 1788

Aged 17. Years.

The headstone inscribed, “Mrs. Temperance”, is a bit confusing. Is this meant as an insult, or as praise? The headstone doesn’t display any given name, or family name, just the nickname.

Mothers dying during child birth were not entirely uncommon, and mom and infant were buried together. One multiple burial under a single headstone was from a regular to the cemetery, a bloodline of record, “Titus.” “James, Ira, & Clary Titus” comprised a triple burial on one very small headstone. A family of three died simultaneously? I have no idea how that occurred, but it sounds very ominous.

People dying in their twenties, thirties, and forties, were not unusual at all. Making it to one’s eighties was rather uncommon. The big mystery is if those who died young, died of natural causes, or not. Without getting too morbid: Were fires, mental illness, alcohol, or violence, a significant problem back then? They were supposed to be very religious, so maybe they just fell ill.

As interesting as the Huntington graves are, the Hampton “Good Ground” settlements predated Western Suffolk by close to a hundred years. From Europe, the Twin Forks would be the first stop, not interior Huntington.

Heading out to the Southern Fork of the East End would be worth a trip. Rolling into East Hampton on Montauk Highway, there is a significant, near four-hundred-year-old burial plot with a nearby reflection pond.

| Behold as you pass by, 1740 | There are angel of death, and crucifix-topping headstones. This is the only fleur-de-lis-topped headstone, the lone French man. | |

| Early medical malpractice: Death by small pox inoculation. | Clarissa, Relief of Amos Platt Lord I commit my soul to thee, Accept the sacred trust: Receive this nobler part of me, And watch my sleeping dust. |

|

| An “associator” fought for the British. | “Sir, [deference to God?] in memory of Adaline, the daughter...” (No, the filigree is so refined, the word “In” looks a lot like “Sir.”) | |

| Elizabeth passed on much too soon, at age 28, “departed in the confident assurance of an immediate entrance to endless joy.” | ||

| In 1764, Peleg Potter died before his time, age 13: “Here lies the youth most loved, the son most dear. Who ne’er knew joy, or friendship might divide. Or gave his father grief, but when he died.”. |

||

The carving is incredibly well-crafted, yet it is from 1764. Long Island does not have quarries, so where was this shale-like stone quarried? | ||